Albert RUBEN

Albert Ruben was born on January 1,1930, in PriStina, to father Immanuel Ruben and mother Gracija, nee Montiljo.He has two sisters who survived the Holocaust He attended primary school in Pristina and, in Belgrade after the war, he completed plumbing trade school by attending evening classes.

During the war he was in Bergen-Belsen with his mother and sisters. His father was expelled from the country to Albania, to Berat, at the very beginning of the war.

Following the liberation he returned to PriStina, then moved to Belgrade. He fled to Italy, via Zagreb, and then to Nahariya in Israel.

He now lives in Milan in Italy. He has one son and four grandchildren.

WHEN THE LIVING ROBBED THE DEAD

We were one of the Sephardic families in PriStina where, before the war, there were about six hundred Jews, but only about a hundred and eighty of them returned from the camps after the war.

All the Jewish festivals were commemorated in our house. We honoured the traditions. I remember my father's mother, although I rarely went to her place. I must have been naughty because she would spank me from time to time, so I didn't visit her very often. She died two months before we were interned in the camp. The PriStina rabbi, Zaharije Levi, shared the same fate, he died a few months before my grandmother, in 1943.

In 1941 I was in Belgrade. I was going to school and living with father’s niece Sofija Ruben, in Sarajevska Street. She had a mixed gods shop. Before the bombing of Belgrade, at about the end of March 1941, I fled to Pristina. At the beginning of the war, the Albanians sided with the Germans. A large number of Albanians flood- eiiZThe city from all directions. They immediately began harassing Serbs and Jews. We lived in a back house. In front of us there was a house owned by an Albanian, a good man so they didn’t burgle our house and they didn't come to harass us. Before the war, Pristina had a population of about eighteen thousand and we all knew one another. There were a lot of Turks there, and very few Albanians.

None of the Jews wore the yellow sign, so nor did anyone from my family, including me. At the end of 1941, my father was taken to intern- ment in Berat in Albania. The Italians were there, and it was easier. In Berat, the internees had to report to the Questura every week, but even this was not so strict.

Mother, my elder sister Matilda, my younger sister Flora and I were left in Pristina. It wasn't difficult for us to obtain food. There was food, but there was no freedom. There was fear. I was afraid of the Albanians and Turks and of being beaten by them. They caught me once, there were three or four of them against me. They beat me seri- ously, causing internal bleeding. After that, I decided to spend less time on the streets. They didn't bully women so much but, on the other hand, they went out less often.

The Germans were the first to come to Pristina. Six or eight months later they surrendered power to the Italians, who were easier to deal with. We were in the town until the end of 1943. When the Germans returned, following the capitulation of Italy, many Albanians put on SS uniforms and became members of the SS army. Some Jews who had fled to Albania earlier now returned to Pristina.

At the end of 1943, it was already winter, maybe November or December, the SS men came to all Jewish homes to round us up. They got us out of our beds and took us straight to the barracks near the football field. There were a lot of us, more than four hundred people. We stayed there for two days. Everyone brought some food with them. We didn't have a toilet, so we dug a hole and put some wooden boards over it. They were threatening us, telling us to hand over our gold and other valuables, and we were throwing them into the toilet. What we had not given to the poor earlier we were now throwing into the toilet.

Before long they put us into cattle wagons and drove us to the Belgrade camp for Jews at the Sajmiste. The Ustasa and the Germans were there. There were political prisoners there when we arrived and also many men and women. I knew one Serb who managed to escape from the Sajmiste camp at night. He swam across the Sava river and reached the other bank, in Belgrade. We spent seventeen days in Sajmiste. Males aged over seventeen were beaten day and night. We ate locust-tree leaves and there was also grass. The food they gave us was mostly potato peel and pea husks. Instead of soup they would give us some black water, so for me the leaves were like baklava.

In Sajmiste they loaded us into wagons. They gave each of us a piece of lard because we had "dry intestines". They gave us this delib- erately in order for us to get diarrhoea so that our conditions would be unbearable. There were about fifty of us in each wagon, people barely had room to sit and it was certainly not possible to lie down and sleep. There were many elderly people with us. Josif Levi, the son of Zaharije Levi and himself a rabbi, was with me in the same wagon, as were his mother and sister. Josif was undertaking rabbinical studies in Sarajevo. They killed his sister Gizela while we were in Sajmiste. They shot her on the bridge. There were three people shot dead on this occasion. The first was an elderly Jewish man, 106 years old, his surname was Mandil. I know his son's name was Rahamim and his grandson was called David. David was killed by a firing squad in Albania. He was in the Partisans and was caught and shot in 1943. The second was Gizela Levi, the rabbi’s sister, whose nerves were shattered. The third was Dzenka Koen. She was about twenty and was an invalid because she had drunk caustic soda in 1943, in an attempt to kill herself, but they had saved her. The three of them were shot dead on the bridge. This happened in December, 1943.

While we were in Sajmiste, the British bombed the camp. This is when my neighbour from PriStina, Into Judic, was killed. His wife and two children remained with us. I don't think the British knew they were bombing us.

In the cattle wagons we had no water or food, only the lard. We reached Dresden. Once we were there, people from the Red Cross gave us some soup and parcels containing a little sugar and some biscuits. From there we travelled to Bergen-Belsen. The journey lasted about eight days because the Allies kept bombing the railway line and it always took a long time for them to fix it.

We got off at the station and all headed on foot to the camp First we were put into part of the camp which was for quarantine. These were barracks with triple bunk beds. In those first days they gave us better food and told us that conditions would be far better in the labou camp. However things were far worse for us. Everyone born before 1930 started working. I didn't have to work, I just dragged cauldrons full of food in the mornings, at noon and in the evenings. There were three of us who did this job. I was in the middle because I was the strongest and the two weaker ones were on the sides. Every day we had mangel-wurzels and chamomile tea without sugar in the morning and evening.

All the inmates in Bergen-Belsen were living corpses, zombies, the living dead. They could barely walk. Each morning at six we had to go outside for them to count us and a list of those unable to attend the roll call had to be given to them. It was very cold and we were all lightly dressed The living would grab from the dead any clothing and shoes that were any good Each day two of us would take the dead by their hands and arms and throw them into carts, then - straight to the crema- torium. The crematorium operated day and night, we could always see flames and smoke coming from the chimney.

We were in the familien lager. Next to us were Jews from Holland and from Greece. At the end of 1944 Jews from Hungary were also brought in. Anne Frank was in this very camp, in the Dutch barracks, but I knew nothing about her at the time. It was only after me war, when I saw her picture, mat I recognised her and realised who she was.

My older sister Matilda worked in the sewing workshop. They used to unpick and remake army uniforms. Mother also worked there. My younger sister was only six. I remember her crying from hunger.

Two or three months before the liberation of the camp we received packages from the Red Cross. Towards the end of the war the Red Cross toured all the places they were allowed to visit

People were dying every day. I also fell ill from typhus. I think that everyone had typhus. We lay in the barracks without any medicine. Somehow I recovered My mother and sisters too, all of us had typhus and recovered from it There were so many lice, but they didn't bother me so much. They used to tell me that they didn't like my blood.

In April, 1945, they again crammed us into wagons those of us who had stayed alive, and they dragged us hither and thither. The British and the Americans were bombing us from all directions. TheRussians were shooting at us with their artillery. Many people died on the journey. At one station, during heavy bombing, they opened the wagons. One Jewish woman had a big piece of white cloth. She began waving it and the bombing stopped. At this station we found some food, green cheese in wooden boxes. It was good, it saved us.

The Germans were planning to blow up a bridge and the whole train, so they began laying mines. They didn't succeed. The Russians had opened fire from canons and katyushas and were getting closer, so the SS men fled before they had finished mining the bridge. They took the locomotive and made off in it.

We were in the wagons in the middle of some forest when the Russians arrived. They told us that we were free and that we could go wherever we liked. I still had a little strength left so I went into the vil- lage to look for some food. The village was called Trobitz. I was accompanied by Mosa Koen and Aron Avramovic, who was at the time called Bahar (he changed his surname in Israel). After the war I gave the daughter of his brother, Jakov Bahar, her name - Ermoza.

After the liberation we stayed in Trobitz for another five months, until October. There we recuperated on three meals of potatoes a day. We returned to the country from the town of Forst, on the Polish border.

This time we were travelling in passenger wagons, about twelve days to Subotica through Czechoslovakia and Hungary. In Subotica we again had to go into quarantine. But there we had everything, both food and money. After that we travelled to Pristina, via Skopje. We arrived in Skopje late in the afternoon. It was Erev Yom Kippur. We all pushed our way into the synagogue, where we also spent the night. Unfortunately there were no Skopje Jews. We ate, washed ourselves and the fast began. The following day, at about eleven in the morning, I told my mother that I was hungry. She replied by saying that it was Yom Kippur when everyone fasts and that, if I wanted to, I could take food myself but that she would not give me any because she did not want to sin. She told me: "Son, hold out if you can, not because of religion, but so that you remember everything we have been through." I still do this, even today, every Kippur.

I went to Italy in 1946 and, on March 6, 1948, before the procla- mation of the Israeli state on May 15,1 went to Israel, straight to the front I was married in 1979 and had a son, Immanuel, and four grand- children.

We were one of the Sephardic families in PriStina where, before the war, there were about six hundred Jews, but only about a hundred and eighty of them returned from the camps after the war.

All the Jewish festivals were commemorated in our house. We honoured the traditions. I remember my father's mother, although I rarely went to her place. I must have been naughty because she would spank me from time to time, so I didn't visit her very often. She died two months before we were interned in the camp. The PriStina rabbi, Zaharije Levi, shared the same fate, he died a few months before my grandmother, in 1943.

In 1941 I was in Belgrade. I was going to school and living with father’s niece Sofija Ruben, in Sarajevska Street. She had a mixed gods shop. Before the bombing of Belgrade, at about the end of March 1941, I fled to Pristina. At the beginning of the war, the Albanians sided with the Germans. A large number of Albanians flood- eiiZThe city from all directions. They immediately began harassing Serbs and Jews. We lived in a back house. In front of us there was a house owned by an Albanian, a good man so they didn’t burgle our house and they didn't come to harass us. Before the war, Pristina had a population of about eighteen thousand and we all knew one another. There were a lot of Turks there, and very few Albanians.

None of the Jews wore the yellow sign, so nor did anyone from my family, including me. At the end of 1941, my father was taken to intern- ment in Berat in Albania. The Italians were there, and it was easier. In Berat, the internees had to report to the Questura every week, but even this was not so strict.

Mother, my elder sister Matilda, my younger sister Flora and I were left in Pristina. It wasn't difficult for us to obtain food. There was food, but there was no freedom. There was fear. I was afraid of the Albanians and Turks and of being beaten by them. They caught me once, there were three or four of them against me. They beat me seri- ously, causing internal bleeding. After that, I decided to spend less time on the streets. They didn't bully women so much but, on the other hand, they went out less often.

The Germans were the first to come to Pristina. Six or eight months later they surrendered power to the Italians, who were easier to deal with. We were in the town until the end of 1943. When the Germans returned, following the capitulation of Italy, many Albanians put on SS uniforms and became members of the SS army. Some Jews who had fled to Albania earlier now returned to Pristina.

At the end of 1943, it was already winter, maybe November or December, the SS men came to all Jewish homes to round us up. They got us out of our beds and took us straight to the barracks near the football field. There were a lot of us, more than four hundred people. We stayed there for two days. Everyone brought some food with them. We didn't have a toilet, so we dug a hole and put some wooden boards over it. They were threatening us, telling us to hand over our gold and other valuables, and we were throwing them into the toilet. What we had not given to the poor earlier we were now throwing into the toilet.

Before long they put us into cattle wagons and drove us to the Belgrade camp for Jews at the Sajmiste. The Ustasa and the Germans were there. There were political prisoners there when we arrived and also many men and women. I knew one Serb who managed to escape from the Sajmiste camp at night. He swam across the Sava river and reached the other bank, in Belgrade. We spent seventeen days in Sajmiste. Males aged over seventeen were beaten day and night. We ate locust-tree leaves and there was also grass. The food they gave us was mostly potato peel and pea husks. Instead of soup they would give us some black water, so for me the leaves were like baklava.

In Sajmiste they loaded us into wagons. They gave each of us a piece of lard because we had "dry intestines". They gave us this delib- erately in order for us to get diarrhoea so that our conditions would be unbearable. There were about fifty of us in each wagon, people barely had room to sit and it was certainly not possible to lie down and sleep. There were many elderly people with us. Josif Levi, the son of Zaharije Levi and himself a rabbi, was with me in the same wagon, as were his mother and sister. Josif was undertaking rabbinical studies in Sarajevo. They killed his sister Gizela while we were in Sajmiste. They shot her on the bridge. There were three people shot dead on this occasion. The first was an elderly Jewish man, 106 years old, his surname was Mandil. I know his son's name was Rahamim and his grandson was called David. David was killed by a firing squad in Albania. He was in the Partisans and was caught and shot in 1943. The second was Gizela Levi, the rabbi’s sister, whose nerves were shattered. The third was Dzenka Koen. She was about twenty and was an invalid because she had drunk caustic soda in 1943, in an attempt to kill herself, but they had saved her. The three of them were shot dead on the bridge. This happened in December, 1943.

While we were in Sajmiste, the British bombed the camp. This is when my neighbour from PriStina, Into Judic, was killed. His wife and two children remained with us. I don't think the British knew they were bombing us.

In the cattle wagons we had no water or food, only the lard. We reached Dresden. Once we were there, people from the Red Cross gave us some soup and parcels containing a little sugar and some biscuits. From there we travelled to Bergen-Belsen. The journey lasted about eight days because the Allies kept bombing the railway line and it always took a long time for them to fix it.

We got off at the station and all headed on foot to the camp First we were put into part of the camp which was for quarantine. These were barracks with triple bunk beds. In those first days they gave us better food and told us that conditions would be far better in the labou camp. However things were far worse for us. Everyone born before 1930 started working. I didn't have to work, I just dragged cauldrons full of food in the mornings, at noon and in the evenings. There were three of us who did this job. I was in the middle because I was the strongest and the two weaker ones were on the sides. Every day we had mangel-wurzels and chamomile tea without sugar in the morning and evening.

All the inmates in Bergen-Belsen were living corpses, zombies, the living dead. They could barely walk. Each morning at six we had to go outside for them to count us and a list of those unable to attend the roll call had to be given to them. It was very cold and we were all lightly dressed The living would grab from the dead any clothing and shoes that were any good Each day two of us would take the dead by their hands and arms and throw them into carts, then - straight to the crema- torium. The crematorium operated day and night, we could always see flames and smoke coming from the chimney.

We were in the familien lager. Next to us were Jews from Holland and from Greece. At the end of 1944 Jews from Hungary were also brought in. Anne Frank was in this very camp, in the Dutch barracks, but I knew nothing about her at the time. It was only after me war, when I saw her picture, mat I recognised her and realised who she was.

My older sister Matilda worked in the sewing workshop. They used to unpick and remake army uniforms. Mother also worked there. My younger sister was only six. I remember her crying from hunger.

Two or three months before the liberation of the camp we received packages from the Red Cross. Towards the end of the war the Red Cross toured all the places they were allowed to visit

People were dying every day. I also fell ill from typhus. I think that everyone had typhus. We lay in the barracks without any medicine. Somehow I recovered My mother and sisters too, all of us had typhus and recovered from it There were so many lice, but they didn't bother me so much. They used to tell me that they didn't like my blood.

In April, 1945, they again crammed us into wagons those of us who had stayed alive, and they dragged us hither and thither. The British and the Americans were bombing us from all directions. TheRussians were shooting at us with their artillery. Many people died on the journey. At one station, during heavy bombing, they opened the wagons. One Jewish woman had a big piece of white cloth. She began waving it and the bombing stopped. At this station we found some food, green cheese in wooden boxes. It was good, it saved us.

The Germans were planning to blow up a bridge and the whole train, so they began laying mines. They didn't succeed. The Russians had opened fire from canons and katyushas and were getting closer, so the SS men fled before they had finished mining the bridge. They took the locomotive and made off in it.

We were in the wagons in the middle of some forest when the Russians arrived. They told us that we were free and that we could go wherever we liked. I still had a little strength left so I went into the vil- lage to look for some food. The village was called Trobitz. I was accompanied by Mosa Koen and Aron Avramovic, who was at the time called Bahar (he changed his surname in Israel). After the war I gave the daughter of his brother, Jakov Bahar, her name - Ermoza.

After the liberation we stayed in Trobitz for another five months, until October. There we recuperated on three meals of potatoes a day. We returned to the country from the town of Forst, on the Polish border.

This time we were travelling in passenger wagons, about twelve days to Subotica through Czechoslovakia and Hungary. In Subotica we again had to go into quarantine. But there we had everything, both food and money. After that we travelled to Pristina, via Skopje. We arrived in Skopje late in the afternoon. It was Erev Yom Kippur. We all pushed our way into the synagogue, where we also spent the night. Unfortunately there were no Skopje Jews. We ate, washed ourselves and the fast began. The following day, at about eleven in the morning, I told my mother that I was hungry. She replied by saying that it was Yom Kippur when everyone fasts and that, if I wanted to, I could take food myself but that she would not give me any because she did not want to sin. She told me: "Son, hold out if you can, not because of religion, but so that you remember everything we have been through." I still do this, even today, every Kippur.

I went to Italy in 1946 and, on March 6, 1948, before the procla- mation of the Israeli state on May 15,1 went to Israel, straight to the front I was married in 1979 and had a son, Immanuel, and four grand- children.

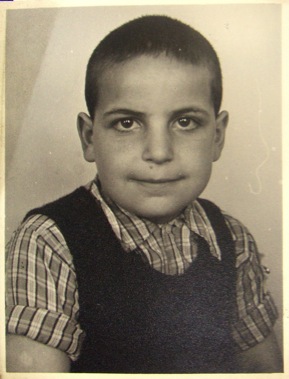

A rare photograph of Albert Ruben

from his childhood days